Hong Kong Inland Revenue Department's latest FAQ: How to determine tax residency for "dual city living"?

Recently, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Hong Kong) Inland Revenue Department updated its Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) to address individuals who may be considered residents in both Mainland China and Hong Kong. The update explains how to determine tax residency status based on the tie-breaker rules under the Arrangement for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes on Income (the “Comprehensive Arrangement”).

As economic exchanges between the two regions become increasingly close, cross-border work and residence have become commonplace, with many people living “working in Hong Kong, residing in Mainland China.” When an individual meets the residency criteria in both jurisdictions, the applicable tax rules and the tie-breaker rules play a crucial role. Click here to read the original article.

Overview of Tax Arrangements between Mainland China and Hong Kong

Mainland China:

A Mainland tax resident individual is defined as a person who has a domicile in China or, if without a domicile, has resided in China for a total of 183 days or more in a tax year. “Domicile” is generally understood as a habitual residence in China due to household registration, family, or economic interests. In practice, habitual residence is the core standard, and holding a household registration (hukou) in Mainland China is likely to be presumed as an indication of habitual residence, thus leading to a tax residency status in Mainland China.

Hong Kong:

A Hong Kong tax resident individual is generally someone who usually resides in Hong Kong, or who stays in Hong Kong for more than 180 days in a relevant tax year, or more than 300 days in two consecutive tax years. Compared to Mainland China, Hong Kong’s criteria focus more on actual residence and economic ties rather than legal permanent residency or household registration status.

Given the objective differences in residency determination and tax year calculation, cross-border workers may qualify as residents in both jurisdictions simultaneously, leading to conflicts in tax residency status. On August 21, 2006, Mainland China and Hong Kong officially signed the “Comprehensive Arrangement” to avoid double taxation and prevent tax evasion. Since then, both sides have signed multiple protocols to update the content, aligning with international tax standards and promoting economic and investment exchanges.

Tax Residency Determination Logic: Tie-breaker Rules

To resolve conflicts in tax jurisdiction, the “Comprehensive Arrangement” introduces the tie-breaker rules, which are widely used in international taxation to resolve dual residency issues caused by differing national laws.

Under the “Comprehensive Arrangement,” for individuals who qualify as residents in both Mainland China and Hong Kong, their tax residency is determined in the following order:

-

Where they have a permanent home;

-

The jurisdiction with which they have closer personal and economic ties;

-

The jurisdiction where they habitually reside;

-

If unresolved, the competent authorities of both sides will negotiate to determine the residency.

It is important to note that these criteria are listed in order of priority, and the subsequent criteria are only used if the previous ones do not resolve the issue.

FAQ Update: How the Tie-breaker Rules Apply in Practice

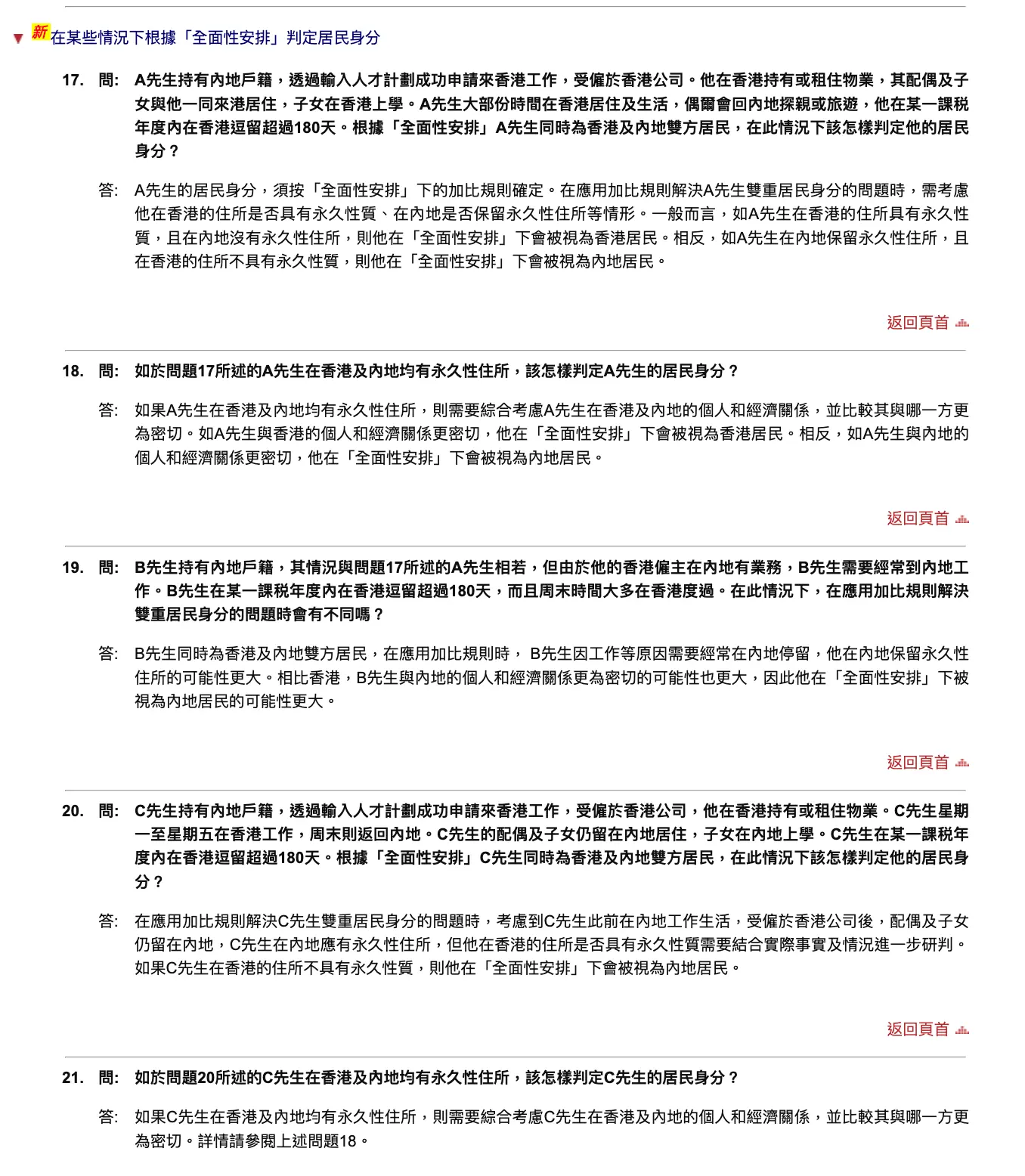

The significance of this FAQ update lies in illustrating, through more realistic cases (Q17-Q21), how to determine an individual’s tax residency in common scenarios such as “talent programs” and “dual-city living.”

For various situations, the Hong Kong IRD does not provide absolute answers on residency status. Instead, it lists factors that may be considered, including: Mainland household registration; long-term residence, work, or study in the core family members’ location (spouse, children); ownership of business equity; place of salary payment and social security contributions. These factors serve as strong evidence of “close economic interests.”

Therefore, having household registration in Mainland China or staying in Hong Kong for more than 180 days in a tax year alone does not automatically determine residency under the tie-breaker rules. Under the “Comprehensive Arrangement,” an individual may still be regarded as a Hong Kong resident. This does not mean that “length of stay” and other core standards are unimportant; rather, the tie-breaker rules require a comprehensive assessment of multiple factors.

Summary

Overall, the recent update from the Hong Kong IRD is not a major systemic change but a practical guide that clarifies the rules for determining tax residency for frequent cross-border individuals. As tax enforcement capabilities improve and information transparency increases, tax authorities in both regions will be better equipped to accurately assess the economic interests of individuals, leading to more precise cross-border tax management.