Barclays report interprets Federal Reserve Chair Powell's "conspiracy": not shrinking the balance sheet but shortening bond durations will trigger a rate cut storm

Barclays’ latest report indicates that Kevin Warsh, who is poised to take over the Federal Reserve, may reshape the Fed’s balance sheet through a “short-term to long-term” strategy—not by reducing the overall size, but by significantly compressing the duration of holdings. This move would rely on cooperation from the Treasury Department to issue more short-term Treasury bills (new agreements), but even so, it would still elevate the term premium of both long- and short-term bonds, forcing the Fed to hedge with “lower interest rates,” potentially triggering a shift in investment that exceeds market expectations for rate cuts. This article is based on a piece by Yang Chen published on Wallstreetcn, translated and refined by Dongqu Dongqu.

(Background: Breaking news! Trump nominates Kevin Warsh to lead the Federal Reserve, increasing the probability of a June rate cut approaching 50%)

(Additional context: The Fed’s leadership change in 2026: the end of Powell’s era, with U.S. interest rates possibly being “cut all the way down.”)

Table of Contents

- Unsustainable Current Conditions: Warsh’s View of the “Abnormal” Balance Sheet

- Hard Landing Risks: Why a Simple Restart of Quantitative Tightening (QT) Is Not Feasible

- Warsh’s “Surgical Knife”: Buying Short-Term Treasury Bills to Shorten Duration

- Key Game: The “New Agreement” Between the Fed and the Treasury

- Endgame Scenarios: Steeper Yield Curves and Lower Rates

Warsh believes the Fed’s balance sheet is “overly bloated and too long in duration,” and hopes to coordinate with the Treasury to shift holdings from long-term bonds to short-term Treasury bills on a large scale. This operation would push up the term premium of bonds, thereby forcing the Fed to lower policy rates.

According to Barclays’ February 10 rate research report:

To reduce the Fed’s footprint in the market without triggering a liquidity crisis, the Fed is likely to stop focusing on shrinking the total balance sheet and instead reinvest maturing bonds into short-term Treasury bills, thereby lowering the portfolio’s duration.

This “short-term for long-term” strategy appears as an asset swap on the surface, but in essence, it shifts the large duration risk back to the private market, triggering a re-pricing of the term premium.

To mitigate the sharp rise in long-term yields caused by supply shocks and prevent a tightening of the financial environment, the Fed would need to cut short-term policy rates to balance the impact. The core logic is as follows:

Unsustainable Current Conditions: Warsh’s View of the “Abnormal” Balance Sheet

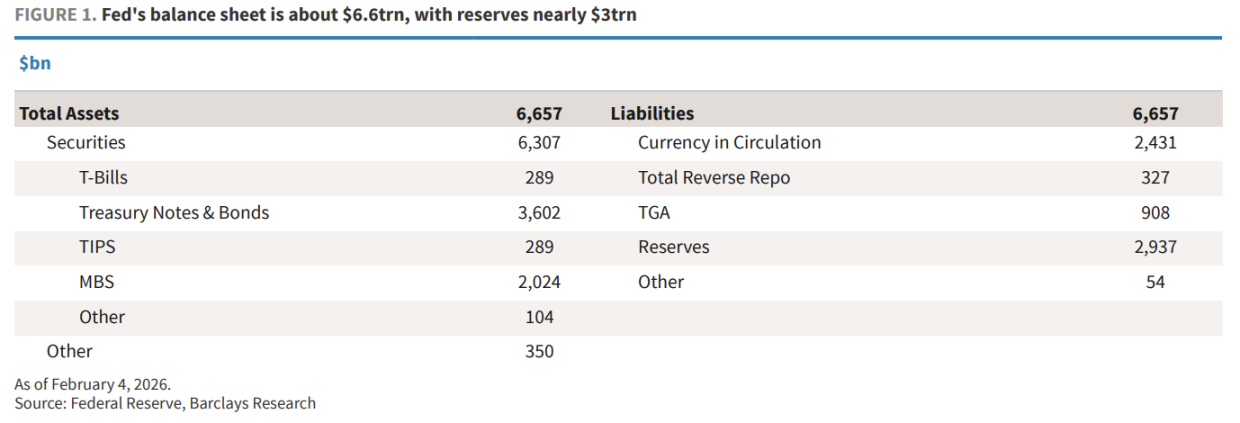

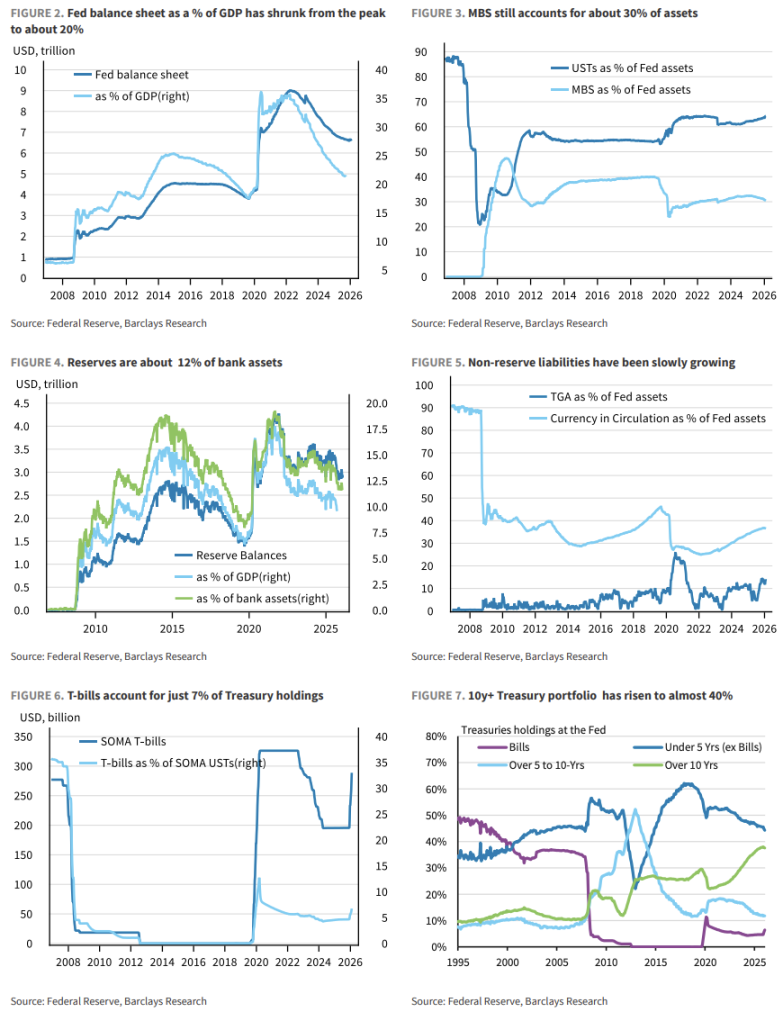

By early 2026, the Fed’s balance sheet will be about $6.6 trillion, far above the pre-pandemic $4.4 trillion and the $0.9 trillion before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Barclays points out that what’s even more intolerable for the “hawkish” Warsh is its structural issues:

- Excessive size: Reserve balances approach $3 trillion, accounting for 12% of bank assets.

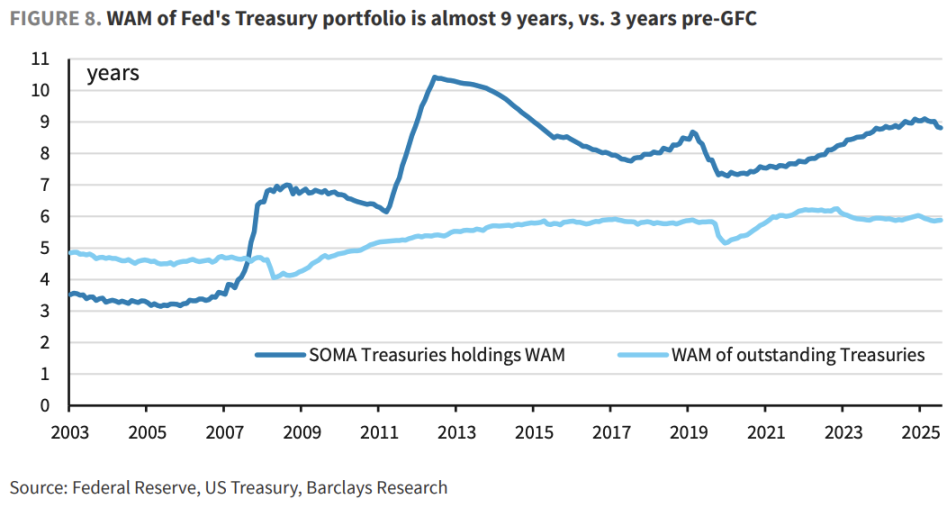

- Too long in duration: The weighted average maturity (WAM) of the bond holdings is about 9 years, compared to just 3 years before the GFC.

- Imbalanced holdings: Bonds over 10 years now make up 40%, while short-term T-bills only account for 7% of the bond portfolio (versus 36% pre-GFC).

Warsh has publicly stated: “The Fed’s bloated balance sheet… can be significantly slimmed down.” He longs for a return to a period of less market intervention by the Fed.

Hard Landing Risks: Why a Simple Restart of Quantitative Tightening (QT) Is Not Feasible

If Warsh attempts to cut assets by suspending the Reserve Management Purchases (RMPs) or restarting QT, the risks are considerable.

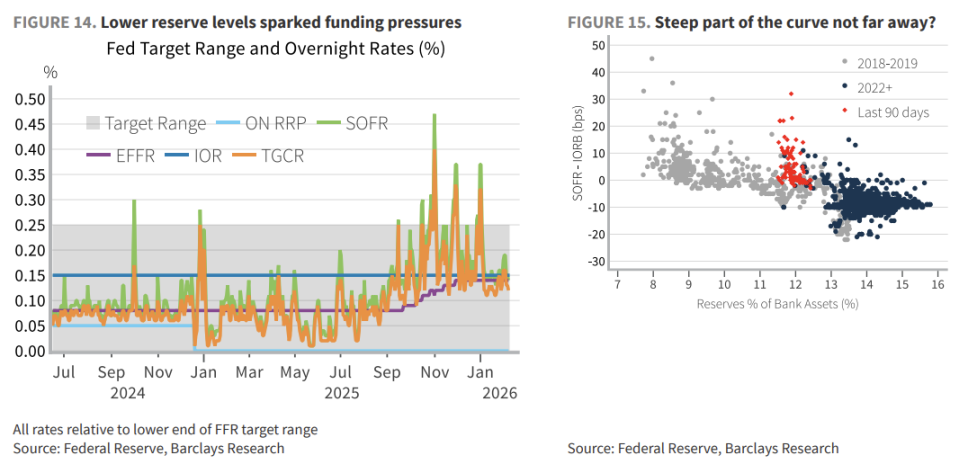

Currently, the banking system operates under a “ample reserve” framework. Banks’ demand for reserves is driven by liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), internal risk management, and payment needs—this is not a linear function but a nonlinear, unpredictable curve.

As evidenced by the September 2019 repo market crisis, once reserve levels hit a scarcity threshold, funding pressures can explode instantly.

If the Fed forcibly reduces reserves, it could unexpectedly push the demand curve into a “steep” zone—causing overnight rates to spike, panic de-leveraging, and ultimately forcing the Fed to step back into the market as it did in March 2020. This would completely contradict the original intent of balance sheet reduction.

Warsh’s “Surgical Knife”: Buying Short-Term Treasury Bills to Shorten Duration

Since outright asset sales are off the table, Warsh’s alternative is to shorten duration.

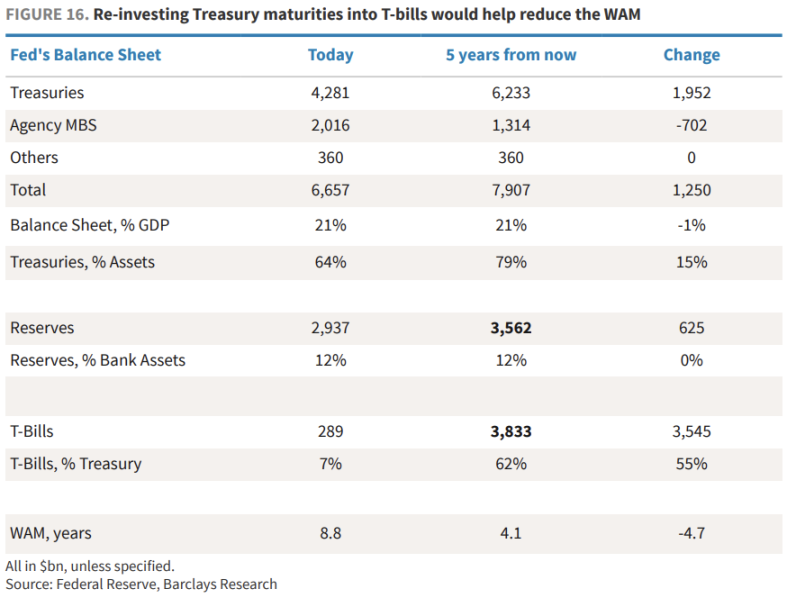

Barclays models a core strategy: the Fed would cease reinvesting maturing medium- and long-term notes/bonds into similar assets, instead reallocating via the secondary market into short-term Treasury bills.

Over the next five years, about $1.9 trillion of notes/bonds will mature. If the Fed implements this strategy, its holdings of T-bills could jump from the current $289 billion to approximately $3.8 trillion, making up about 60% of the bond portfolio. The portfolio’s duration would fall from 9 years to about 4 years, approaching pre-GFC levels.

This move would significantly reduce the Fed’s interest rate risk exposure and leave more room for future policy maneuvers.

Key Game: The “New Agreement” Between the Fed and the Treasury

However, the effectiveness of this strategy depends on Treasury cooperation—what Warsh calls the “New Accord.”

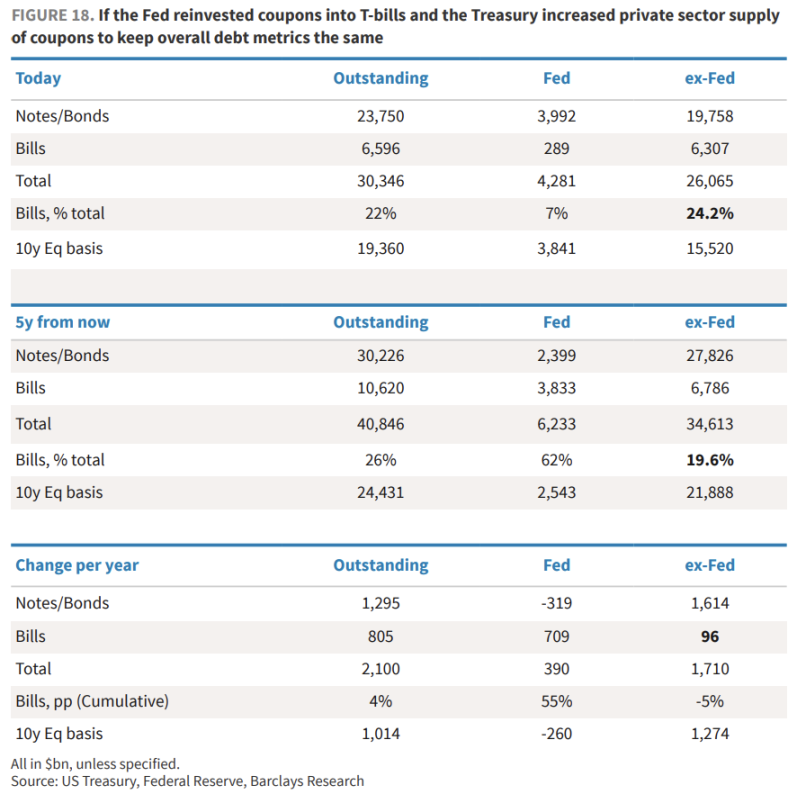

Scenario A: A “Disaster” Without Coordination

If the Fed stops purchasing long-term bonds at auctions, and the Treasury issues more long-term debt (coupons) to fill the gap, the private sector would have to absorb an additional roughly $1.7 trillion of long-duration supply (equivalent to 10-year maturity).

This would cause a severe imbalance in long-term U.S. debt supply and demand, sharply increasing the term premium—Barclays estimates a 40-50 basis point rise in 10-year yields.

Scenario B: Achieving a “Silent Understanding”

A more ideal path is for the Treasury to keep issuing long-term debt at current levels and instead increase short-term T-bills to meet the Fed’s new demand. Under this scenario, the private sector’s T-bill holdings would stabilize around 24%.

Although the average maturity of overall debt would shorten from 71 months to about 60 months, this approach would effectively avoid market turmoil.

Endgame Scenarios: Steeper Yield Curves and Lower Rates

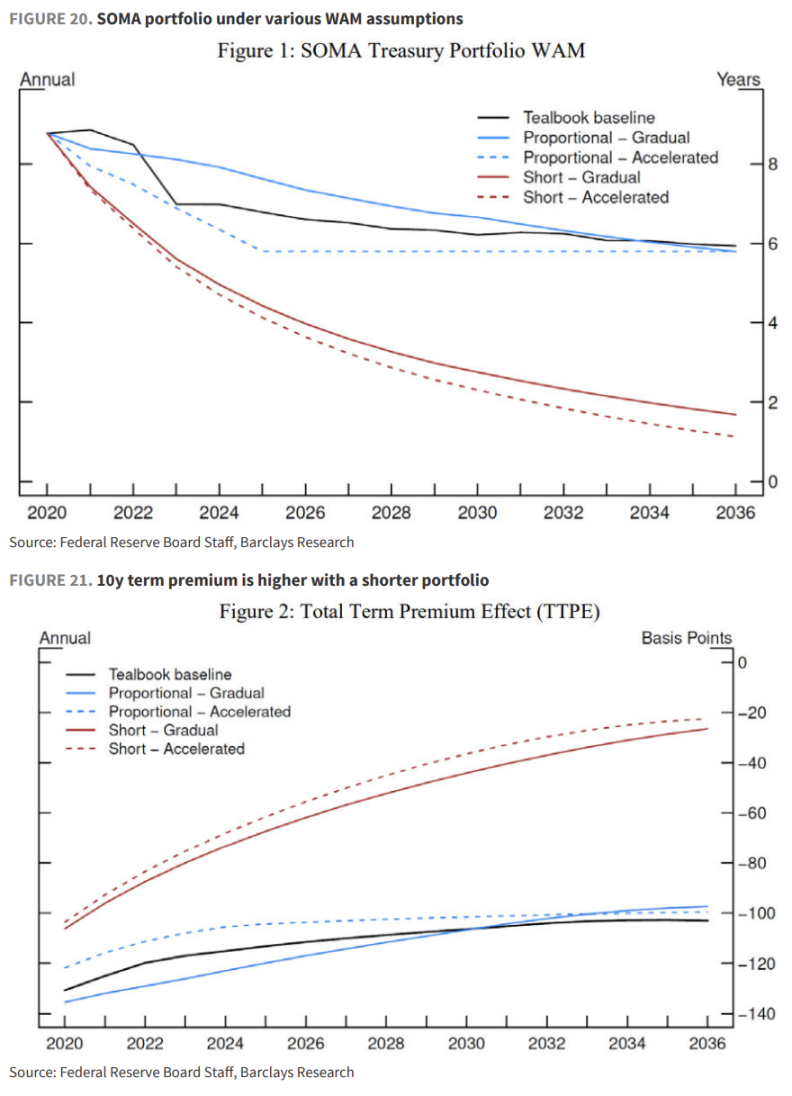

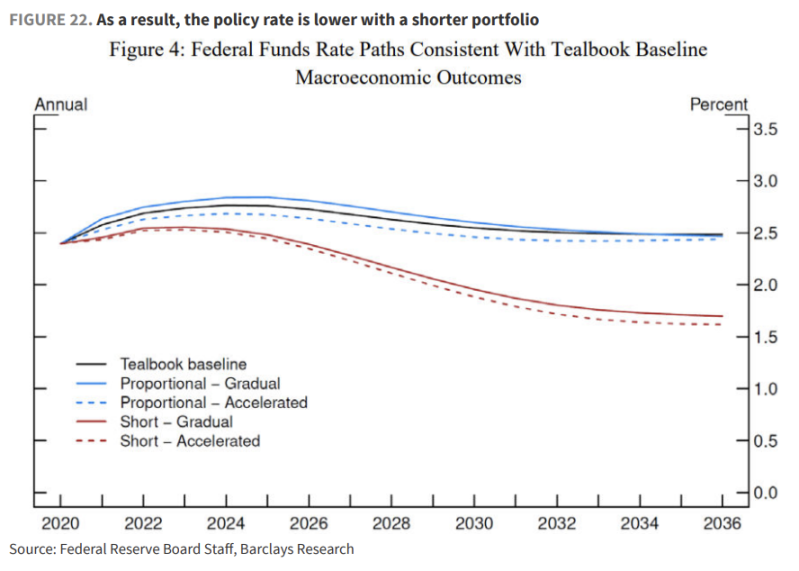

Barclays cites a 2019 study by Fed staff, which yields a counterintuitive but crucial conclusion: shortening the portfolio’s duration effectively acts as a form of rate hike, requiring the Fed to lower policy rates to hedge.

Modeling shows:

- Rising term premiums: Even with Treasury cooperation, increased supply of duration risk during the transition would push up term premiums.

- Rate cuts as compensation: To maintain the same overall economic output (inflation and unemployment unchanged), if the Fed adopts a short-duration portfolio, the federal funds rate would need to be 25 to 85 basis points lower than the baseline.

Barclays emphasizes that Warsh’s normalization of the balance sheet is a multi-year, long-term process. Investors will face: higher repo risk premiums (due to Fed probing reserve limits), steeper yield curves (reflecting increased term premiums), and lower policy rates (to offset financial tightening).

For investors, this means favoring front-end assets (betting on larger-than-expected rate cuts) while remaining cautious on the long end (demanding higher risk premiums).